With the abysmal state of healthcare in this country, it shouldn’t be surprising that tech companies—specifically those in the app space—have swooped in left and right to solve the ills that the federal government can’t or won’t. Want to monitor your blood pressure? There’s an app for that. Mental health got you down? There are apps for that, too. And of course, there are apps to ease of the multimillion-dollar headache plaguing the country at large: health insurance. And none is more popular than GoodRX. It’s ranked at the top of the Apple App Store, has more than 450,000 five star ratings, and is—for roughly 10 million users per month, per the company’s own metrics—the key to getting the prescriptions you need at prices you can afford.

Hell, before becoming gainfully employed, I used this app to shave off hundreds from my prescriptions for the psychiatric drugs I need to function, day in and day out. What I didn’t realize at the time is that every prescription refill comes with more than a few strings attached.

Because I cover the app space thoroughly, I’ve learned to be skeptical of everything I download on my phone—but for some reasons, I was still shocked to see, with my own two eyes, multiple ad networks getting their hands on my very personal data—including my specific prescriptions. As I dug deeper, what became even more shocking was that this wasn’t only 100 percent legal, it was 100 percent legal because it exploited very obvious loopholes in government regulation—and the internet itself.

“Nothing happening here is illegal, it’s just taking advantage of the system,” Hined Rafeh, a PhD candidate at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute researching on medical data regulation, told me. “We’re in a system where people are faced with the reality that ‘a doctor says I need to take this, I can’t afford it, but this company says that they’ll help me—and it looks like they have everything in their privacy policy, so it should be okay.’”

It is, in fact, more than okay. In GoodRX’s own privacy policy, the company begins by thanking users for “placing your trust” in the company.

“We understand that your personal information is sensitive, and also that privacy policies and legalese can be scary, so we want to thank you for trusting GoodRx with your information,” the policy reads, before going on to state:

GoodRx does not sell personal medical information. We do not provide your personally-identifiable medical information to third parties in exchange for payment.

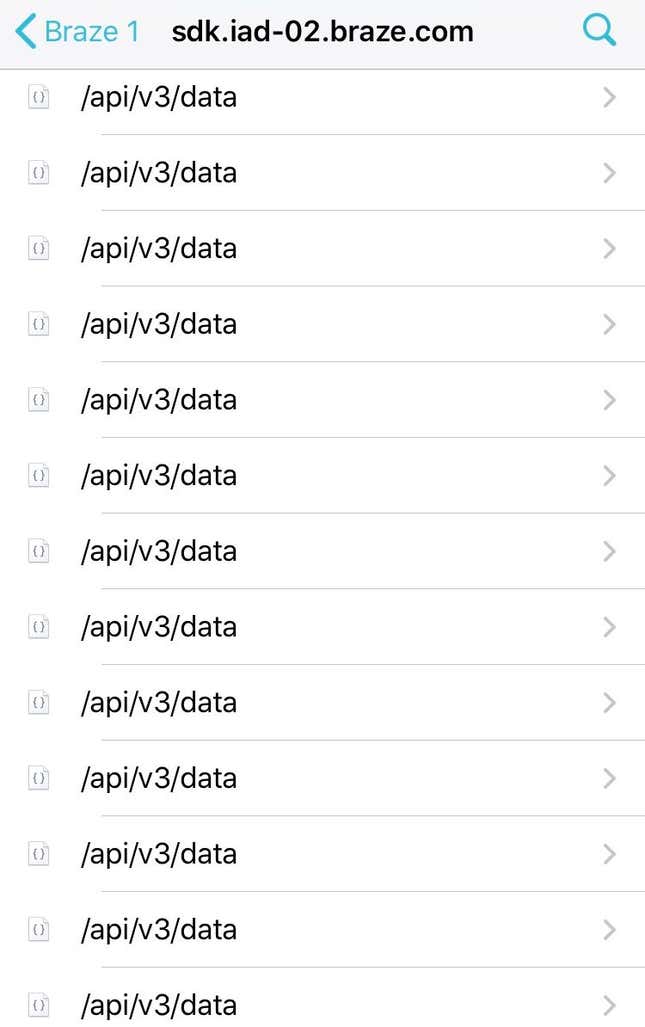

First, let’s crack open the idea of “personally identifiable” information. As I’ve tackled before, the idea of what is and isn’t “personally identifiable” from a legal POV is effectively meaningless. While looking over the data being shared from GoodRX’s app, I found it was being sent to four separate companies: Branch, which links users across their different devices, and Facebook both received my usage information, like how often I opened or closed the app. Braze, which helps advertisers target people across the internet, and Google Analytics received more invasive-seeming data, including the name of my pharmacy and my specific prescriptions.

Whether or not this data is explicitly “identifiable”—tied to something like my name or home address—is pretty much moot, since it is being tied to my individual device. But because these device identifiers aren’t considered “identifiable” even under the strictest data privacy law in the U.S.—despite the fact that these identifiers can literally be used to pinpoint a person’s precise location, among other sensitive details—these apps get a free pass. And that’s not the only free pass they get.

“In my research, health data is data that is used or taken by a hospital from a patient—that data doesn’t include consumers,” Rafeh explained. “But when looking at companies like 23andme, for example, they do the same exact tests that a hospital does. But their data is consumer data.”

She’s right. When I reached out to the Food and Drug Administration to get to the bottom of whether the pharma data being sent back and forth between GoodRX and these marketing companies could legally be considered “health data” covered under HIPAA, a spokesperson replied that “this is actually out of the purview of the FDA,” and directed me to the Department of Health and Human Services’ “Office for Civil Rights.” There, a 2016 guide for app developers tangling in the healthcare space specifically outlines how apps like GoodRX don’t have to comply with HIPAA, the federal law that governs health information privacy:

Only health plans, health care clearinghouses and most health care providers are covered entities under HIPAA. If you work for one of these entities, and as part of your job you are creating an app that involves the use or disclosure of identifiable health information, the entity (and you, as a member of its workforce) must protect that information in compliance with the HIPAA Rules.

As Rafeh explained to me, HIPAA came into being to protect confidentiality between doctors and their patients—not between a private company and a consumer. As she put it, an app that you’d use to communicate directly with a doctor, or directly with a hospital, or directly with an insurance company would need to fall in line with HIPAA. But an app like GoodRX, which tracks drug prices and gives users coupons for discounted medicine, can have relatively free rein over your health-related data since it’s a private company—no doctors or hospitals involved.

In the absence of guardrails from the FDA, these app developers are technically required to abide by the Federal Trade Commission’s privacy guidelines, which haven’t been updated since 2016. These recommendations, meanwhile, point app developers back to the FDA’s guidance surrounding the issue, while also giving a free pass to apps that hoover data that’s been reasonably “de-identified,” without offering a substantial definition for what that even means. When I asked about their policies surrounding health-related apps specifically, the FTC didn’t respond.

“It’s this shitty feedback loop where the customers are confused about what health data is, and they’re constantly misinformed, and it’s definitely intentional,” Rafeh said. “But at the same time, it’s kind of like, the laws are there. This isn’t a secret.”

Whether this confusion is “intentional” is certainly up for debate, but this much is clear: There’s a lot of money riding on the answer. Over the past few years, the market for DTC—or direct to consumer—healthcare has exploded into a multi-trillion dollar industry that’s caught the attention of the biggest names in tech, with Google and Facebook, and Amazon dipping their toes into the field in recent months. While GoodRX is quiet about its own financials, leaked investor documents point to a roughly $3 billion valuation in 2018—a value that undoubtedly balloons with every acquisition the company makes.

“We strive to go above and beyond both legal requirements and consumer expectations when it comes to protecting consumer data,” GoodRx told me in a statement. In response to questions both from Gizmodo and Consumer Reports, the company also rolled out a standalone page on their site describing the appointment of a new “VP of Data Privacy” to “coordinate between engineering, marketing, and other teams to ensure we only share what’s necessary and always act in our users’ best interests.”

Of course, GoodRx isn’t alone—recent numbers point to big pharma turning their attention away from advertising in print and on television, and more advertising where most of us spend our time: the internet. And while healthcare still takes up a substantially smaller chunk of the digital marketing pie than, say, retail, that number is growing, with recent numbers pointing to the industry spending roughly $2 billion to reach consumers on their phones alone, according to research from eMarketer.

And that’s ultimately where my data comes in. While looking at the data being sent from GoodRx to some of the major names in tech—Facebook and Google, along with Braze and Branch, two companies specific to the adtech space—most of the data being sent back and forth was pretty basic. Metrics like how often I opened the app, how long I was spending browsing around for different prices, and so on.

Tracking my precise prescriptions—which seemed like the juiciest data nugget of all—seemed to be almost like an afterthought. An incredibly creepy afterthought, but an afterthought nonetheless.

As GoodRx explained in a statement, “personal medical information”—including the names of prescriptions—were never shared with Facebook, “even in encrypted form.” When this data was shared with Google, meanwhile, they stressed that this intel is “de-identified,” stressing that the company doesn’t “use medical information to target advertising on Google.”

Because of the incredibly opaque way data moves from our phones through the internet and into major advertising platforms, those of us concerned about the specific details of digital privacy are often left with the frustrating reality of taking companies at their word. I can crack open an app with some helpful tools and see that my extremely personal prescription data flowing into these ad pipelines, and I can see multiple companies passing off this unencrypted intel, but that’s it. Even efforts on GoodRx’s part to allow consumers to remove their data from this cash-grab ecosystem doesn’t actually do anything, because ultimately, even opening the app will just start the cycle over again. Perhaps more troubling is the fact that simply downloading GoodRx, whose whole value proposition is saving its users money, is valuable intel for advertisers who are trying to target people based on what they can afford. Knowing that I was a consumer on the “lower-income” side is likely more valuable than knowing that I regularly “use antidepressants.”

And with healthcare costs on the rise with every passing month, it’s unlikely that any of us who use GoodRx already will be deleting the app for good anytime soon.